Narrative: Alice Paul

- I can analyze Alice Paul’s story as an example of facing adversity and choosing to act responsibly.

Essential Vocabulary

| responsibility | To strive to know and to do what is best rather than what is most popular or expedient. To be trustworthy for making decisions in the best long-term interests of the people and tasks of which one is in charge. |

| heckled | To interrupt a speaker at a public event. |

| plight | A difficult situation. |

| concoction | Another word for a mixture of things. |

| jeers | Another word for insults. |

| rebuffed | An unkind rejection. |

Narrative

For decades after the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, woman suffrage leaders such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Lucy Stone took responsibility in the struggle for women to vote. They made different arguments for suffrage, but the central claim on the right to vote was equality in exercising consent in republican government. By the beginning of the twentieth century, a new generation of leaders demonstrated responsibility as they marched, lobbied, and spent time in prison fighting for equality.

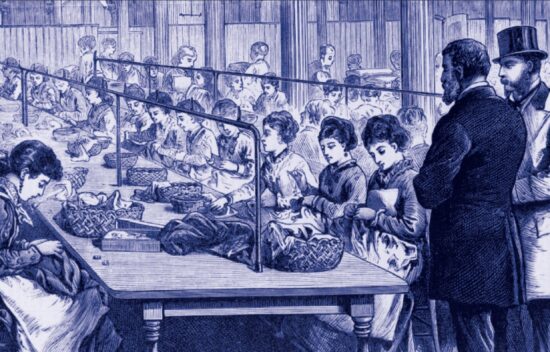

Alice Paul was one of those leaders who showed determination and pushed the movement in a more radical direction. Paul was born to privilege as the daughter of a wealthy Quaker banker. She studied sociology and social work at elite colleges such as Swarthmore, the University of Pennsylvania, and the London School of Economics at a time when women (and most men) were rarely admitted to college. She was a progressive reformer who always assumed responsibility to help others. She worked at a New York City settlement house that sought to improve conditions and provide services for workers and immigrants in urban areas during an age of expanding industry. .

While studying in England, Paul found her calling. She devoted herself completely to the cause of woman suffrage. She attended rallies held by Emmeline Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) and soon joined the cause selling newspapers and speaking on a soapbox on street corners. Soon, she was joining in more drastic measures to bring attention to the movement.

Paul joined with American suffragette, Lucy Burns, and others following the prime minister and cabinet officials to urge their support. They interrupted speeches, heckled the politicians, shattered stained-glass windows, and shouted “Votes for Women” at the audiences. They were arrested and chose a sentence of hard labor for a month to demonstrate their plight.

During her time in prison, Paul participated in a hunger and clothes strike. Wrapped only in a blanket, she endured the cold and was weakened from several days of not eating. Prison authorities had the doctors force-feed a concoction of eggs and milk through a long tube inserted into her nostril. She persevered through the adversity and showed her willingness to suffer for women’s equality.

In 1910, Paul returned to the United States and earned a doctorate from the University of Pennsylvania. Two years later, she and Burns joined the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), which was led by Anna Howard Shaw. NAWSA pursued a state-by-state strategy for woman suffrage because the Constitution left voting eligibility to the states.

The strategy was bearing fruit, especially in western states, as Wyoming (1869), Utah (1870), Colorado (1893), and Idaho (1896) granted woman suffrage before the effort stalled and proposals lost in some states. From 1910 to 1912, Washington, California, Oregon, Arkansas, and Kansas approved woman suffrage. Nevertheless, Paul and Burns urged an alternative path.

Paul and Burns were members of NAWSA but organized the Congressional Committee (CC) in Washington, D.C. They advocated for a federal amendment for woman suffrage. Despite moving in a different direction within NAWSA, they joined the woman suffrage march during Woodrow Wilson’s presidential inauguration. The committee flier for the event read, “We march today to give evidence to the world of our determination that this simple act of justice be done.”

On March 3, 1913, Paul marched with 8,000 women dressed in white who were carrying American flags and “Votes for Women” banners. The marchers in the parade suffered jeers, curses, and even violence from a hostile crowd of onlookers. Paul and other leaders were invited to the White House to meet with the new president. Wilson thought it was mostly a state issue due to federalism and brushed the request for support aside.

Paul persisted in her activism for woman sufferage. She joined other suffragettes meeting several more times with Wilson and with members of Congress. They marched to the Capitol and presented signed petitions to Congress asking for the right to vote. They were rebuffed time and again but refused to quit.

That year, Paul continued to push in a different direction within NAWSA. The CC changed its name to the Congressional Union (CU) and focused on a federal amendment. She started a weekly newspaper, The Suffragist. The first issue asserted that woman suffrage was “the elementary question of self-government for the women of America.” Later that year, the CU split with NAWSA over their irreconcilable strategic visions. Paul was unafraid to chart her own path for equality.

In 1916, Paul created the National Woman’s Party (NWP) wholly dedicated to the single issue of woman suffrage. That year, Carrie Chapman Catt, the leader of NAWSA, decided that the organization would adopt the amendment strategy. Late in the year, the House Judiciary Committee reported an amendment to the entire House of Representatives.

Still, Paul did not relent in publicizing the cause with suffragette marches in the capital. In early 1917, as the United States moved closer to intervention in World War I, she arranged for continuous daily parades past the White House. The banners had democratic slogans such as, “Governments Derive Their Just Powers from the Consent of the Governed” and “How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?” She was arrested several times that summer and fall and participated in more hunger strikes.

In January 1918, the House voted for a woman suffrage amendment by the constitutional requirement of a two-thirds majority, but the Senate delayed action. Even though the president had no constitutional role in the amendment process, Wilson shifted to support the amendment publicly. He told the Congress, “The least tribute we can pay them is to make them equals of men in political rights as they have proved themselves their equals in every field of practical work they have entered.”

In May and June 1919, the House and Senate passed the woman suffrage amendment. The Constitution required that three-fourths of the states must ratify the amendment. On August 18, 1920, Tennessee became the thirty-sixth state to ratify the amendment and make it part of the fundamental law of the land. The Nineteenth Amendment read, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

Alice Paul exhibited the civic virtue of responsibility as she spent more than a decade organizing, marching, and suffering so that women could vote in the United States. Paul saw it as her responsibility to stand up for woman suffrage, even if it meant personal sacrifice. Her sense of responsibility was a testament to her dedication to the idea that American women should be able to participate in the civic life of republican government by voting and offering their consent to the laws under which they lived.

Analysis Questions

- For what cause was Alice Paul working?

- What can you infer about Paul’s experience with force-feeding in England?

- Paul returned to the U.S. in 1910 after her stay in England. As a member of the National Woman’s Suffrage Association (NWSA), she scheduled a parade to coincide with President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. The parade was not without its challenges. Men shoved and tripped the marchers, while police did little to assist. One hundred marchers were taken to the hospital. How do you think the virtue of responsibility helped Paul work to overcome the challenges of facing a hostile crowd?

- The parade got the president’s attention. Paul went to the White House two weeks later, and the president promised to give the idea of voting rights for women his “most careful consideration,” but this promise did little to satisfy Paul. Should she have let that conversation be the end of it?

- Paul and the 500 others who were arrested for speaking, publishing, peaceably assembling, and petitioning became known as political prisoners. Why might Wilson have ordered the suffragists to be released from prison?

- If you were writing a eulogy for Alice Paul, what would you say, and why? How should Paul’s efforts on behalf of woman suffrage be remembered?

- Identify two other examples of responsibility in United States history. How has responsibility on the part of individuals helped the United States to be the kind of nation its founders envisioned? How can responsibility play a part in maintaining our republic?