The Stono Rebellion

Written by: Bill of Rights Institute

By the end of this section, you will:

- Explain how enslaved people responded to slavery

Suggested Sequencing

This Narrative should follow the Origins of the Slave Trade Narrative in Chapter 1.

The white planters and farmers on the Stono river near Charleston, South Carolina, had reason for concern in the late summer of 1739. A smallpox epidemic had raged through the area the previous year, and yellow fever was spreading. The settlers expected a bumper rice crop of about 35 million pounds for export, but it was hurricane season and they watched the weather closely. Conflict with Spain, Britain’s imperial rival, also caused talk of war to increase in the port city. Most ominously, the settlers were concerned about a recent proclamation from Spanish Florida offering freedom to their runaway slaves.

The Spanish proclamation went into effect in 1733, but it was enforced only with the arrival of a new Florida governor, Manuel Montiano, in 1737. The previous year, seventy slaves from South Carolina had traveled over water and land as they fled successfully to Florida and freedom. South Carolina planters generally had large plantations of several hundred acres to raise labor-intensive rice and indigo. The wealthier ones owned hundreds of African slaves, who outnumbered white settlers in the colony. Poorer farmers had smaller farms and fewer slaves but were just as interested in controlling the slave population through a variety of means, including whipping, slave patrols, and a version of Christianity that promoted obedience.

Slaves worked in the colony according to a “task system” in which they completed their work at their own pace under the watchful eye of an overseer. Compared with enslaved people in other regions, they had a fair amount of autonomy to determine the means by which they would labor for their masters. The presence of fewer Europeans enabled these Africans and African Americans to shape their own communal culture in the fields and in their quarters during time off for the Sabbath on Sunday. They resisted the slave system by feigning illness, running away for a few days, or breaking farming implements. But violence ultimately controlled slaves and compelled their labor. Meanwhile, slave owners lived in constant fear that their slaves would revolt and kill them, because they were greatly outnumbered. In August 1739, the colonial assembly passed a law requiring planters to go to church armed in case of a slave revolt or an escape.

Sometime after midnight on September 9, about twenty slaves working as a crew on a drainage ditch decided to escape to freedom in Florida. Many were Angolans and were led by an enslaved man named Jemmy. They broke into Hutchenson’s general store for the arms and gunpowder sold there. Somehow, they were discovered by two white men, Robert Bathurst and a Mr. Gibbs. The slaves killed the men and left their heads on the front steps. There was no turning back.

Moving out into the night without a plan, the armed slaves first came upon the home of a planter named Godfrey. They plundered the house and killed Godfrey and his two children before setting fire to the dwelling. With the flames rising, they continued their march southward. Before dawn they reached Wallace’s Tavern, where they drank briefly but heartily and spared the owner because he was known to be kind to his slaves. They proceeded to sack the nearby home of a Mr. Lemy, killing him, his wife, and their child before setting the house ablaze.

The emboldened slaves traveled along the road, burning six more houses and killing several of the white inhabitants, whether wealthy planters or poor farmers. Some of the slaves in the plantations hid their masters and even drove off the rebels, either too frightened to join the rebellion or genuinely concerned for their owners. Other slaves, however, joined the rebels, whose ranks grew to fifty or sixty.

As dawn broke, the rebels boldly marched down the road waving a banner and beating a drum to signal other slaves to rebel. They even loudly cried out the word “liberty” for anyone to hear. Destruction was evident in their wake, with flames and smoke rising high into the sky across the landscape. Just then, Lieutenant Governor William Bull and a small group of white planters coincidentally riding along the road spied the formation. Realizing what was happening, Bull and his outnumbered companions wheeled their horses and fled, narrowly eluding capture and sounding an alarm as they went.

As they marched several more miles, the rebels were joined by additional runaways and numbered almost one hundred. Exhausted from their journey, they stopped in a field to rest, celebrate their freedom, and wait for more of their fellow slaves to join the escape. But suddenly, a group of dozens of armed and mounted white planters converged on them from the south with murderous intent.

The slaves grabbed their muskets and fired a few hasty shots. The planters descended upon the slaves, dismounted, and loosed a devastating volley into their ranks. After the exchange of gunfire, fourteen slaves were dead or wounded. In the confusion, about thirty escaped into the countryside. Some of the surviving runaways were summarily executed or questioned and then killed. The planters allowed others to return to their plantations and await their fate. Some were killed by their masters; others were whipped and sent back to the fields.

In the coming weeks, patrols roamed the countryside in a fierce manhunt to capture the runaways. Whites even employed some friendly American Indians to track them. About a week later, whites discovered a group of ten runaways and killed them in a pitched battle. Georgians over the border were on high alert at their forts and plantations. Eventually, all the rebels were either killed or returned to slavery. Slaves who had protected their masters during the rebels’ march received gifts of money and clothing.

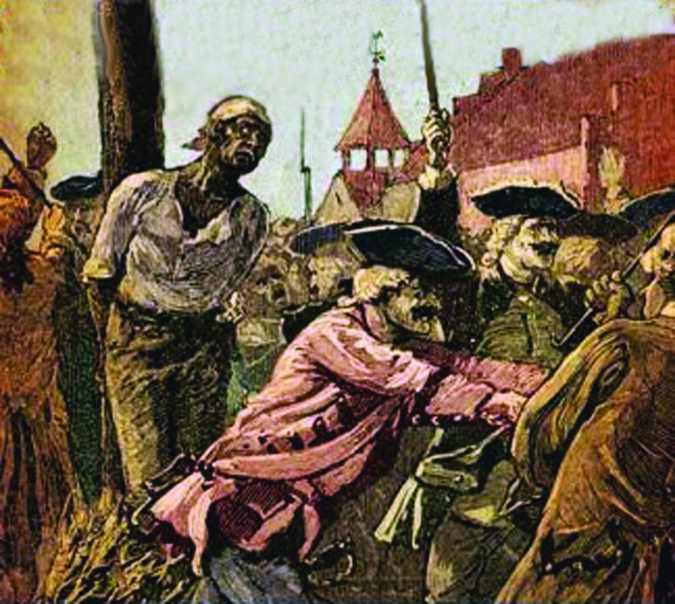

A grim fate often awaited slaves who were recaptured in the aftermath of rebellions. The man pictured here was one of thirteen burned at the stake after a slave rebellion in New York City in 1741, two years after the Stono Rebellion.

In October, the colonial assembly met and discussed the events that unfolded during the Stono slave revolt. Several revisions were made to the colony’s slave code in hope of preventing future revolts. Masters were not to work slaves on the Sabbath; they had to provide slaves with adequate food and clothing and could not murder them. At the same time, the colony tightened restrictions on slaves, banning the sale of alcohol to them, not allowing them drums, and preventing masters from teaching them to read or write.

The largest and most significant slave rebellion in the British North American colonies, the Stono Rebellion revealed tensions that continued in slave states throughout the next century. Slaves were oppressed by a brutal system of forced labor and sometimes violently rebelled. Slave owners, on the other hand, kept a watchful eye and constantly sought ways to keep slaves obedient and accepting of their condition.

Review Questions

1. What was the name of the largest slave uprising in the British North American Colonies?

- Pueblo Revolt

- Denmark Vesey Conspiracy

- Stono Rebellion

- Bacon’s Rebellion

2. Which European rival to the British issued a proclamation enticing slaves to run away to Florida for freedom?

- France

- The Netherlands

- Spain

- Portugal

3. What economic activity in South Carolina relied on slave labor?

- Commercial fishing operations

- Harvesting of lumber for shipbuilding

- Extensive trade of grain crops with other imperial nations

- Farming of labor-intensive cash crops like rice

4. What did not motivate South Carolina slaves to remain subservient to their masters?

- Christianity that promoted obedience

- Physical violence

- Slave patrols

- Relative autonomy on Sundays

5. What allowed enslaved workers to complete their assignments daily and then have time to themselves?

- Gang system

- Task system

- Domestic system

- Debt system

6. Which of the following was a covert way in which enslaved people resisted their forced labor?

- Sabotaging farm tools to slow down work

- Staging direct confrontations over inhumane conditions

- Petitioning the overseer for better treatment

- Threatening violence against owners

7. What best describes the way the Stono Rebellion ultimately ended?

- Almost every rebel successfully reached Florida, gaining freedom.

- An impromptu militia of white planters used weapons to wound and maim the rebellious slaves.

- The South Carolina legislature decreed that all slaves must be emancipated.

- Each rebel was granted the due process of law but was found guilty and executed.

8. Which was not an impact of the Stono Rebellion on the social structure in South Carolina during the middle of the eighteenth century?

- Increased fear among white plantation owners

- Implementation of laws that restricted slave movements and freedoms

- Freedom for those who instigated the rebellion

- Deaths of white people and black people in Charleston

9. What was the immediate impact of the Stono Rebellion on South Carolina?

- Freedom for all the enslaved peoples in the rebellion

- A reorganization of plantation labor to create wage-based jobs

- New laws that attempted to further restrict the autonomy of enslaved people

- Reduced fear among local white planters

Free Response Questions

- Explain the extent to which the Stono Rebellion changed the system of slavery in British North American colonies.

- Explain the circumstances that allowed for the rise of the Stono Rebellion.

AP Practice Questions

“XXXVI. And for that as it is absolutely necessary to the safety of this Province, that all due care be taken to restrain the wanderings and meetings of Negroes and other slaves, at all times, and more especially on Saturday nights, Sundays, and other holidays, and their using and carrying wooden swords, and other mischievous and dangerous weapons, or using or keeping of drums, horns, or other loud instruments, which may call together or give sign or notice to one another of their wicked designs and purposes. . . .

XLII. . . . That no slave or slaves shall be permitted to rent or hire any house, room, store or plantation, on his or her own account, or to be used or occupied by any slave or slaves. . . .

XLV. That all {people}, who shall hereinafter teach or cause any slave or slaves to be taught, to write, or shall use or employ any slave as a scribe in any manner of writing whatsoever, hereafter taught to write, every such person and persons, shall, for every such offense, forfeit the sum of one hundred pounds current money.”

An Act for the Better Orderings and Governing Negros and Other Slaves in this Province, May 10, 1740

Refer to the excerpt provided1. What was the intent of the authors in enacting the legislation cited in the excerpt provided?

- Physical and mental restriction of slaves

- End of the chattel system of enslavement

- Creation of a method for gradual emancipation

- Assurance of better working conditions for slaves

2. The excerpt provided can best be understood in the context of

- the creation of the caste system

- a failed slave revolt

- an impassioned abolitionist movement

- the start of the Civil War

Primary Sources

Governor Bull’s Letter to the Royal Council: https://digital.scetv.org/teachingAmerhistory/lessons/GovBullLetter.htm

A Commons House of Assembly Committee Report: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part1/1h312t.html

Suggested Resources

Hoffer, Peter Charles. Cry Liberty: The Great Stono River Slave Rebellion of 1739. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Kolchin, Peter. American Slavery: 1619-1877. New York: Hill and Wang, 2003.

Wood, Peter H. Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion. New York: Norton, 1974.

Wright, Donald R. African Americans in the Colonial Era: From African Origins through the American Revolution. Arlington Heights: Harlan Davidson, 1999.